*Editor’s note: K-VIBE invites experts from various K-culture sectors to share their extraordinary discovery about the Korean culture.

Doc. Earm’s ‘K-Health’: Health Should Be Studied Like Academics (Part 3)

By Yung E. Earm (Professor Emeritus, Department of Physiology, College of Medicine, Seoul National University; Research Fellow, Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics, University of Oxford )

These days, Korean television—especially cable channels—is overflowing with information about food and health remedies. Some programs even feature doctors explaining in detail how spinal surgeries are performed. I found this quite strange.

Why should a doctor be lecturing on spinal surgery on a TV show? There’s no other country with as many health-related programs as ours. There's a flood of information like "eating this food is good for that part of your body." But can readers really trust all that information?

Regardless of whether it's trustworthy or not, can anyone realistically follow all of it? And if, by chance, all of that information were indeed credible and people followed every piece of it, would nobody ever get sick?

Of course not.

We must also consider indicators beyond physical health. Modern people suffer not only from physical illnesses but also from mental disorders. In particular, more people are taking antidepressants and sleeping pills due to conditions like depression.

Mental health is just as important as physical health, yet in reality, people hesitate to visit a psychiatrist. In Korea, there is a tendency to treat mental illness solely as an individual issue.

But mental illness is not just a personal matter—it is also closely linked to family and society. Many cases show that symptoms improve when a patient is hospitalized for treatment, only to worsen again when they return to their home or social environment. It’s more reasonable to view these conditions as social illnesses. Fundamental treatment is only possible when environmental factors change, but radically changing one’s environment is extremely difficult.

◇ Stress: What Is It Really?

Many people say the biggest enemy of health is stress. But what exactly is stress? When I was a student, stress was defined very narrowly. It referred to a psychological or physical state of tension when placed in a difficult-to-adapt environment. For example, suddenly announcing a pop quiz in a classroom or hanging a mouse in a corridor for everyone to touch as they pass—these are direct, visible stimuli that cause immediate tension, and they were considered stress.

Nowadays, however, stress can come from a boss who never leaves work, a growing waistline, or ever-rising prices.

The word "stress" originates from the Latin word stringere, meaning "to tighten." It was originally a term used in physics to describe the internal force that resists external pressure or deformation.

It was Dr. Hans Selye, an endocrinologist at the University of Montreal in Canada, who began using this term in a medical context. In 1936, he defined stress as "the response of the body to any demand placed upon it in order to maintain stability when psychological or physical balance is threatened."

After conducting experiments on live rats, Dr. Selye concluded that stress is a major factor in the development of diseases.

He categorized stress into two types. "Eustress" is initially burdensome but ultimately has a positive effect on one’s life. "Distress" persists despite efforts to cope and results in anxiety, depression, or other negative symptoms.

The important takeaway here is the concept of eustress. Most modern people view stress as entirely negative, but the truth is, stress can have a positive impact. Moderate tension brought on by stress can inject vitality into life and increase productivity and creativity at work.

Not just the type, but also the amount of stress matters. Too much or too little stress can be harmful. Excessive stress can lead to sudden death from arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, or stroke. You’ve probably seen scenes in dramas where a CEO hears shocking news and clutches their chest before collapsing.

On the other hand, too little stress can weaken the immune system. For instance, lab animals raised in sterile environments with no external stressors show very little immune development. When exposed to germs, they die quickly from infection.

Likewise, children who are overprotected in ultra-clean environments tend to have weaker immune systems. With too little stress, they become more vulnerable to infections.

That’s why a moderate amount of stress should be regarded as a necessary lubricant for life.

Of course, most stress that modern people experience is distress, which is difficult to cope with or adapt to. Chronic stress becomes especially problematic because it disrupts the body’s homeostasis—its effort to maintain consistent levels of blood pressure, blood sugar, and body temperature.

Temporary stress goes away once the cause disappears, allowing the body to recover quickly. But chronic stress continuously disrupts homeostasis, having significant effects on health.

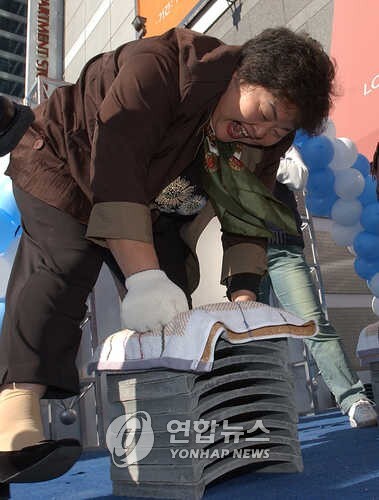

|

| ▲ A housewife participates in the Housewife Stress Relief Tile-Breaking Contest, held at Lotte Department Store Gwanak Branch in Seoul on November 16, 2003, by striking a roof tile with all her strength. (Yonhap) |

◇ How Does Stress Work?

Stress refers to the body’s overall reaction to internal and external environmental changes. The body responds in various ways, but the main reactions are through the autonomic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.

The autonomic nervous system is made up of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. The sympathetic nervous system triggers stress responses, while the parasympathetic system works to restore the body to its normal state. The HPA axis primarily operates through the action of cortisol, the so-called "stress hormone."

When stress occurs, multiple parts of the brain and the autonomic nervous system secrete stress hormones into the bloodstream, preparing the body to respond. This is known as the stress response.

The first reaction is that the sympathetic nervous system becomes activated, while parasympathetic function decreases.

The sympathetic nervous system focuses on immediate survival, while the parasympathetic system handles long-term planning. So in the face of sudden external stimuli, the sympathetic system must be activated while the parasympathetic is suppressed.

When the sympathetic nervous system is activated, several things happen: pupils dilate, heart rate increases, and arterioles in the skin and digestive tract constrict, causing blood pressure to rise. As a result, blood is redirected from the skin and gastrointestinal tract to the brain, heart, and muscles.

Then, the body uses stored energy to power these functions. Processes like sleep and digestion are suppressed.

On the other hand, when the parasympathetic nervous system is activated, it promotes peace, rest, and preparation for the future. Digestive functions improve, and the heart rate and breathing stabilize. It also promotes sleep. Rather than using nutrients immediately, the body stores them for later.

The activation of the sympathetic nervous system is essential for efficient use of the body’s energy in response to external threats. For example, imagine encountering a wild tiger or lion. The brain must rapidly decide whether to flee or fight, and then it must channel all energy into running or attacking.

Thus, the stress response itself is a vital survival function. The problem arises when stressful situations become chronic or when the stress is not properly managed, leading to dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system.

In such cases, one may develop new illnesses or experience a worsening of existing symptoms, such as headaches, insomnia, anxiety disorders, stress-induced hypertension, irritable bowel syndrome, arrhythmia, asthma, and chronic pain. Prolonged stress can also weaken the immune system, reducing resistance to infection.

(To be continued)

(C) Yonhap News Agency. All Rights Reserved